In the previous episode, we learned how to distinguish languages into families and subfamilies using their morphological characteristics. By the ratio of morphemes per word, there’re the isolating/analytic and the synthetic families. In the synthetic family, there’re two subfamilies: fusional and agglutinative, with respect to the separability of the inflectional affixes. In the synthetic family, there’re also two marking systems: case marking (on the dependents) and head marking (on the heads). We’ve learned a lot about the cases (grammatical functions of nouns) and how they’re used. In this episode, it’s time to learn some more about the grammatical information, a.k.a. category, of the nouns and the verbs.

Nominal categories. Nouns and adjectives are grouped together as nominal because they share common linguistic properties. Some of these properties is worth observing.

- Number: count distinction of nouns. Most languages have the number system of singular (one) vs. plural (more than one). But there’re also other systems such as

- Singular, dual (two), and plural: as in Sanskrit, Ancient Greek, Old English, and other ancient Indo-European. For example, Sanskrit puras ‘person’ > purau ‘two persons’ > purās ‘many persons’.

- Singulative (individual) vs. collective (group): as in Welsh, Standard Arabic, etc. For example, Standard Arabic hajar ‘stone’ (collective) > hajara ‘a stone’ (singulative).

- Singular, dual, trial (three), and plural: as in the pronoun systems of Tok Pisin and several Austronesian languages. No known languages have the trial number in nouns.

- Singular, dual, trial, quadral (four), and plural: as in the pronoun systems of Marshallese, Sursurunga, and several Austronesian languages

- Singular, paucal (small amount), and plural: as in Hopi, Walpiri, Arabic (for some nouns), Polish (for some nouns), Motuna, and Serbo-Croatian. For example, Polish pies ‘a dog’ > psy ‘2/3/4 dogs’ > psów ‘5 or more dogs’.

- Noun class: a division of nouns into classes that form agreement with another aspect of language, such as articles, adjectives, pronouns, or verbs. Common systems of noun classes are masculine-feminine, masculine-feminine-neuter, animate-inanimate, and common-neuter. For example, adjectives decline according to nouns in Latin, e.g. bonus dominus ‘a good master’ (masculine) > bonā puellā ‘a good girl’ (feminine) > bonum castellum ‘a good castle’.

- Definiteness: distinction of entities whether they can be identified in a given context or not. If it can be identified up to the current point of the context, it is definite. Otherwise, it is indefinite. Some languages distinguish the definiteness, while some don’t. For example, in English, definiteness is marked by the determiners. In Germanic languages and Balto-Slavic languages, two sets of adjectives for nouns with different definiteness.

- Numeral classifier: counting words inherent for each noun. Numeral classifiers are prominent features of nouns in many East and Southeast Asian languages such as Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Thai, Laos, Khmer, etc. For example, in Thai, classifier ตัว [tua] is a classifier of animals.

sùnák sǎ:m tua dog three CL ‘three dogs’ Classifiers differ from measure words (like a cup of, a pound of, two kilograms of, etc.) in that the classifiers are inherent to the nouns while the measure words are not.

Verbal categories. Verbs and adverbs are grouped together as verbal because they share common linguistic properties. Some of these properties should be taken into account.

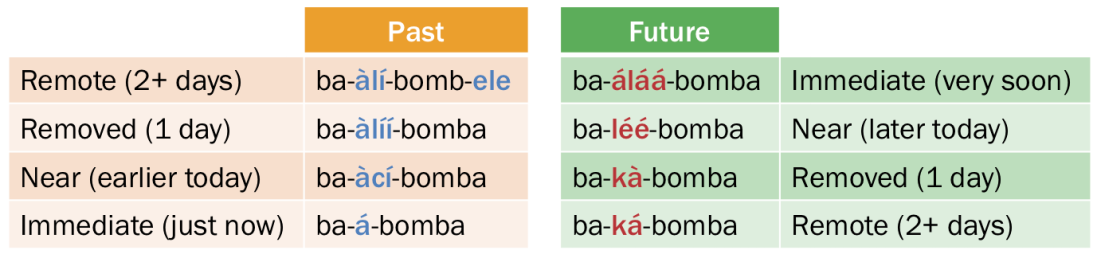

- Tense: a relation of the event time and the speech time. Let’s take a look at Chibemba’s tenses for ba-bomba ‘they work’.

Tense system in Chibemba In Chibemba, there’re three general tenses: present, past, and future. But the past and the future tenses have four levels of remoteness from the speech time: immediate, near, removed, and remote. That is quite tense, isn’t it?

- Aspect: a temporal structure of an event. For example, in English there’re three aspects: perfect, imperfect (a.k.a habitual), and progressive.

- Perfective: “He wrote three novels.”

- Imperfective (habitual): “He writes novels.”

- Progressive: “He is writing a novel.”

- Mood: how the speaker thinks about an event expressed in morphological and syntactic constructions. For example, there’re three moods in English:

- Indicative (assertion): “It is sunny outside.”

- Subjunctive (undertainty): “It should be sunny outside.”

- Imperative (command): “Break the window!”

- Modality: the semantic notion of the mood. For example, there’re four modalities in English.

- Neutral: “I resit the exam.”

- Obligation: “I must resit the exam.”

- Desire: “I want to resit the exam.”

- Possibility: “I may resit the exam.”

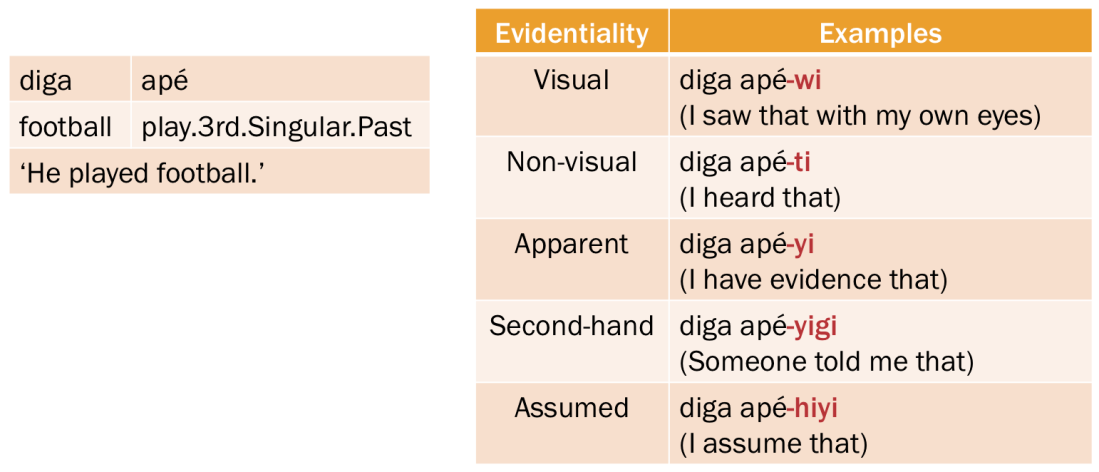

- Evidentiality: the validity of an event. For example, in Tuyuca, a language in Brazil and Colombia, there’re five evidentialities: visual, non-visual, apparent, second-hand, and assumed.

Evidentiality in Tuyuca

Copyright (C) 2018 by Prachya Boonkwan. All rights reserved.

The contents of this blog is protected by U.S., Thai, and International copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution of the contents of this blog without written permission of the author is prohibited.