Last time, we learned how to generalize the patterns of constituents with the Phrase Structure Grammar (PSG). Each constituent consists of two components: the head (the core meaning) and the complement (the rest of the constituent that completes the core meaning). Constituents that function similarly are grouped into a single phrase type. We name that phrase according to its head’s phrase type—the preposition phrase has the preposition as the core meaning, for instance.

Although it’s clear to indicate the head of each phrase, the complement part is still quite problematic. That’s because some elements of the complement are compulsory while the others are omissible. For example, in verb phrase “[ate icecream ravenously]”, the complement ‘icecream’ is necessary for the verb ‘ate’ while the complement ‘ravenously’ can be omitted. We have to disentangle the compulsory from the omissible in order to examine the smallest complete meaning of a constituent. This partition is suggested in Xʹ Theory (Chomsky, 1970).

Xʹ Theory (pronounced ‘X-bar Theory’) states that each constituent consists of four basic components: head (the core meaning), complement (compulsory element), adjunct (omissible element), and specifier (an omissible phrase marker). The name Xʹ (traditionally typesetted as ) comes from an intermediate phrase type that represents the smallest complete core meaning formed by the head of type X and its complements. Here, X is actually a variable for any phrase type or part of speech such as N (noun), V (verb), and P (preposition).

In essense, the theory proposes three steps to help identify the four elements of each constituent.

Step 1. Complementation: the head of type X combines with any number (including zero) of complements to become Xʹ; formulated as:

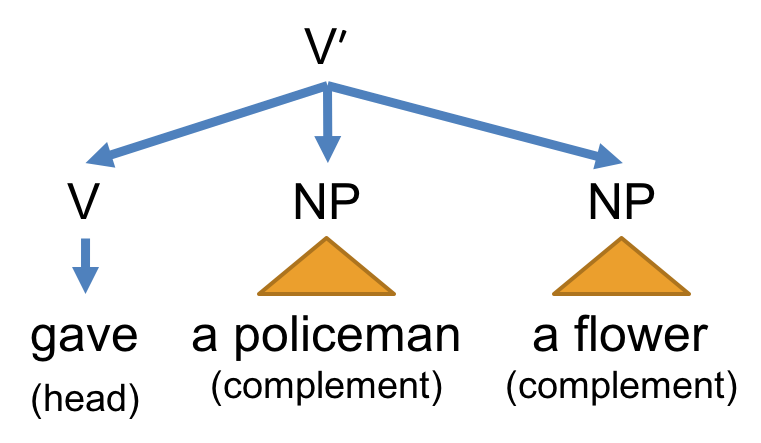

The notation is string concatenation in any order. Note that any constituent of type Xʹ conveys the smallest complete core meaning of the head of type X and it needs not be grammatical. For example, consider the constituent “gave a policeman a flower”. The ditransitive verb ‘gave’ requires two objects—a direct object and an indirect object. When this verb of type V combines with the two complements, i.e. ‘a policeman’ and ‘a flower’, the whole constituent becomes of bare phrase type Vʹ. We sometimes call a constituent of type Xʹ a bare phrase.

Step 2. Attachment: a bare phrase of type Xʹ combines with any number (including zero) of adjuncts to become Xʹ; formulated as:

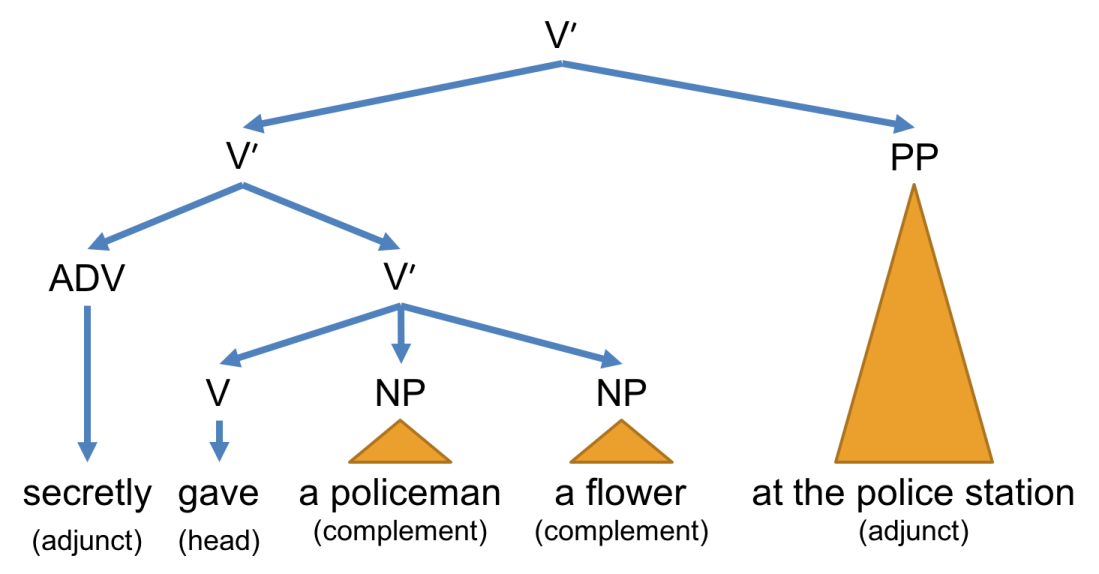

We can attach any number of the adjuncts to a constituent of type Xʹ and it won’t change the phrase type. For example, let’s consider the constituent “secretly gave a policeman a flower at the police station”. When we attach the adjunct ‘secretly’ to the constituent “gave a policeman a flower” of type Vʹ, the whole constituent is still a bare phrase of type Vʹ. The same applies when we attach the adjunct ‘at the police station’ to the whole constituent again. We obtain a bare phrase of type Vʹ.

Step 3. Specification: a constituent of type Xʹ combines with zero or one specifier to become a phrase of type XP; formulated as:

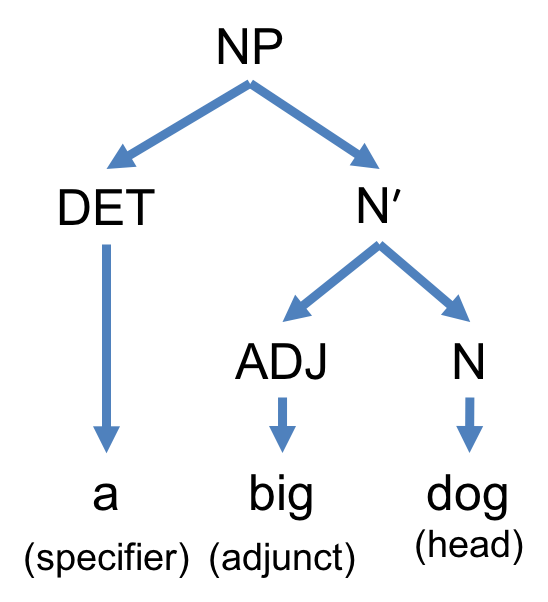

The specifier is a word or a derivational affix that makes a bare phrase of type Xʹ become a fully grammatical phrase of type XP. It’s the word or derivational affix that signifies the beginning of such phrase. In the case of English, the determiners (i.e. a, an, and the) signifies the beginning of a noun phrase. For example, let’s consider the constituent “a big flower”. The head is the noun ‘flower’. Since the adjective ‘big’ is omissible, it’s an adjunct. Their combination ‘big flower’ is of type Nʹ but it’s still ungrammatical. To make it grammatical, we attach the specifier ‘a’ to make it a noun phrase (NP).

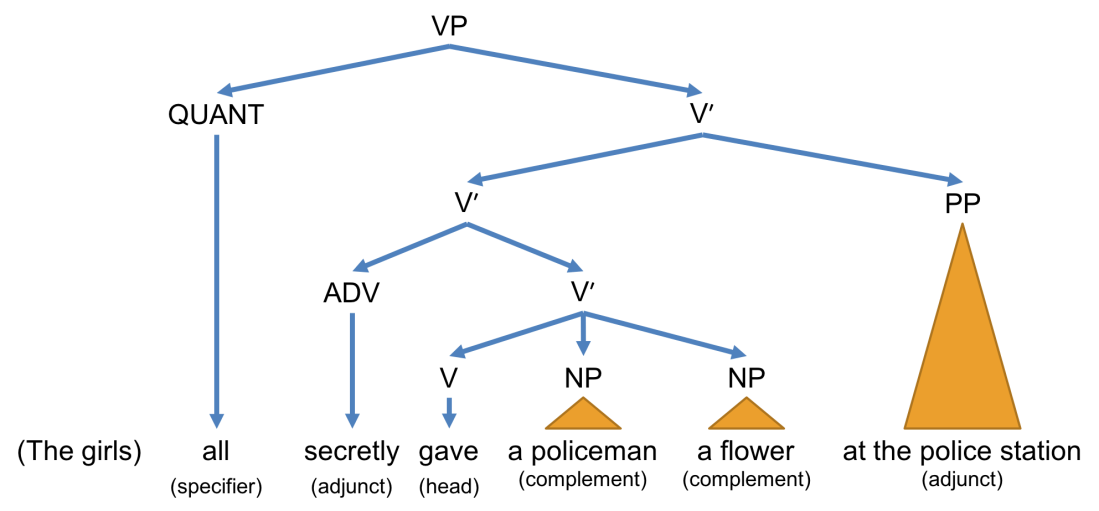

The quantifiers (i.e. all and each) can be a specifier of a verb phrase. In sentence “The girls all secretly gave a policeman a flower at the police station”, the quantifier all becomes the specifier for the constituent “gave a policeman a flower at the police station” of type Vʹ.

Note that the specifiers are omissible. A constituent of type Vʹ can become a fully grammatical verb phrase VP on its own if there’re no quantifiers preceding.

One key advantage of Xʹ Theory is it paves a way to an in-depth understanding of how constituent formation takes place and how to design the part of speech tagset. First, with the head and its complements identified, we can determine the number of arguments for each part of speech tag. For example, we can classify English verbs into three categories: intransitive (requiring zero complements e.g. ‘sit’), transitive (requiring one complement e.g. ‘eat’), and ditransitive (requiring two complements e.g. ‘give’). Second, we can separately treat each adjunct as attachment of a meaning modifier rather than meaning complementation. For example, we don’t have to divide nouns into subcategories with respect to the number of adjectives modifying them. Finally, we can also distinguish the specifiers from the adjuncts and treat them separately. In the case of English, for instance, articles differ from adjectives in that the first transform a bare phrase into a fully grammatical phrase while the latter don’t. In the case of Mandarin Chinese and Thai, on the other hand, there’re no concepts of specifiers, so any full noun phrase is identical to its bare phrase form. Without doubts, the Xʹ Theory is a key foundation of modern syntax theories and we’ll refer to it from time to time.

References

- Chomsky, Noam (1970). Remarks on nominalization. In: R. Jacobs and P. Rosenbaum (eds.) Reading in English Transformational Grammar, 184-221. Waltham: Ginn.

Copyright (C) 2018 by Prachya Boonkwan. All rights reserved.

The contents of this blog is protected by U.S., Thai, and International copyright laws. Reproduction and distribution of the contents of this blog without written permission of the author is prohibited.